Sculpting the Psyche

This article was originally published in Ins&Outs magazine.

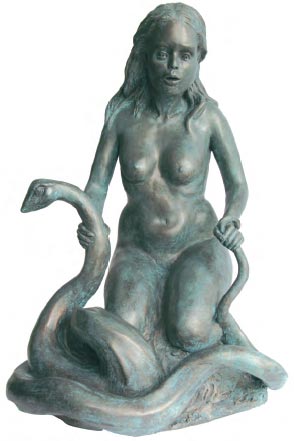

More than ten years ago, Maria Taveras had a distinctive dream while visiting the C.G. Jung Institute in Zurich, in which the image of a woman who was a serpent from the waist down permeated her subconscious, and it wouldn’t rest there.

More than ten years ago, Maria Taveras had a distinctive dream while visiting the C.G. Jung Institute in Zurich, in which the image of a woman who was a serpent from the waist down permeated her subconscious, and it wouldn’t rest there.

That dream told her to sculpt, an art form she was not trained in, and she produced what turned out to be an excellent representation of Melusina, a goddess who is prevalent in French fairy tales. Strangely enough, Taveras was not familiar with the story until after her sculpture was completed.

“These images are archetypal,” the sculptor explained over the phone. “They are relevant to all females.”

Taveras’ career description defies catagorization. She is a Jungian psychotherapist based in New York City; an award-winning sculptor; and a rare example of those things not being mutually exclusive. Fresh from a trip to Cape Town, South Africa, where she was featured as Artist/Jungian Psychotherapist at the 17th Congress of the International Association of Analytical Psychology, she was eager to discuss her unusual and cerebral approach towards sculpting and painting.

Carl Jung, the father of Jungian psychology, formulated the concept of the collective unconscious, also known as the objective psyche. The theory behind it is that all human beings share common experiences through representative archetypes, such as the Old Testament’s figure of Lilith. Jung’s theory goes on to say that the collective unconscious, through dreams, can help guide an individual towards self-realization. Jung defines this as the process by which a person may become who he or she is uniquely in life.

By sculpting dream images, Taveras says she is creating a dialogue between the collective unconscious and her own ego, which moves her toward self-realization, a process that she calls “interactive morphing.”

Taveras’ process is the reason she was invited to the conference in Cape Town, to show them her exhibit of sculptures and paintings, “Foreign Journeys: Dream Art and the Creative Imagination.” It was also the first time artists were invited to bring their work as well. The lecture Taveras gave at the conference described her process of sculpting and painting, and her show there was divided into a series. Whereas one image may have signified a psychological education, the next could have symbolized the completion of a psychic journey.

Taveras’ process is the reason she was invited to the conference in Cape Town, to show them her exhibit of sculptures and paintings, “Foreign Journeys: Dream Art and the Creative Imagination.” It was also the first time artists were invited to bring their work as well. The lecture Taveras gave at the conference described her process of sculpting and painting, and her show there was divided into a series. Whereas one image may have signified a psychological education, the next could have symbolized the completion of a psychic journey.

The rest of the artists represented were South African shamans, now commonly known as indigenous practitioners, who were trained in the traditional methods of healing rituals. Their art consisted of floor paintings and sculptural installations, that, according to Taveras, in their own way could be described as “interactive morphing.”

“The West applies psychological methods consciously, so the rituals (of the indigenous practitioners) are not actually applied literally, like a Jungian psychoanalyst,” she said.

Because the indigenous practitioners’ rituals outdate Jungian psychoanalysis, the contrast between the two is both clear and muddled. Maria Taveras says that postmodern shamanism and Western ideas of consciousness were converging in Cape Town during the conference. She also learned that traditional techniques of indigenous practitioners were still thriving for some native South Africans.

Taveras explains that according to Jung, all cultures have an understanding of the human psyche, and that it’s generally the terms used to describe it which differ. Instead of “collective unconscious,” another term might be the “spirit world.” One major similarity is that an understanding of the human experience can be helped along using a guide, whether it be an indigenous practitioner or a psychotherapist.

Taveras’ own journey toward Jungianism began with a desire to understand Catholicism, a religion she hasn’t taken part in since the eighth grade.

“As a young girl, I used to go to church with my family, and I was curious about why they did the things they did,” Taveras said. “My understanding of their ideas towards females, having to live in a certain way with certain restrictions and rules about how a woman can be … I found it very oppressive and very difficult to live out.”

Jungian theory and sculpting has allowed Taveras to come to terms with her religious past, as well as to undertake her own self-realization. Some sculptures Taveras produces, several of which are made of terra cotta, depict a woman with a serpent flying out of her mouth. Sometimes the serpent has wings and appears to be leaping for freedom. Taveras has found studies written by Jung involving a woman with similar dreams, of serpents in her stomach, which only adds weight to the concept of a collective unconscious. Taveras has since interpreted the expulsion of serpents from her mouth as symbolic of giving birth to creativity through sculpting, as opposed to purging negativity.

Jungian theory and sculpting has allowed Taveras to come to terms with her religious past, as well as to undertake her own self-realization. Some sculptures Taveras produces, several of which are made of terra cotta, depict a woman with a serpent flying out of her mouth. Sometimes the serpent has wings and appears to be leaping for freedom. Taveras has found studies written by Jung involving a woman with similar dreams, of serpents in her stomach, which only adds weight to the concept of a collective unconscious. Taveras has since interpreted the expulsion of serpents from her mouth as symbolic of giving birth to creativity through sculpting, as opposed to purging negativity.

The sculptures and paintings that Taveras depicts from her dreams are representations of very personal transitions; therefore, she doesn’t reveal the true inspiration behind some of her works. However, since they are symbolized by archetypal figures that are a part of the universal unconscious, Taveras feels free to put these pieces on display. In 2004, she showed a terra cotta sculpture entitled “Transformation of the Feminine,” depicting a woman stepping out of a tree. It won a 2004 Gradiva Award from the National Association for the Advancement of Psychoanalysis.

Although she was initially only familiar with painting as an art form, Taveras has since furthered her education in the sculpting realm through classes and private tutors. “They were at a loss initially because it’s such a different way of approaching sculpting,” Taveras says of her teachers. Instead of going about it aimlessly, Taveras worked specifically with her dream images. When sculpting, she tries to apply Jung’s idea of developing a dialog between the collective unconscious and her own ego, so all of the emotions she experiences while sculpting can get reflected in the piece.

“I am applying a psychological method while sculpting. This is very different than most sculptors, so the reward of the conclusion is at once a piece of artwork, but also a psychological process,” Taveras said.

Her patients have also benefited from this unique method of therapy through art. “Most people will respond to this type of therapy, but individuals who have active imaginations engage more easily and fluidly,” Taveras says.

“If they’re depressed or stuck, there might be a poverty of images and the feeling capacity might be numb. But with time and using the same method, they can also be reestablished.”

Taveras’ sculptures will be exhibited at the Archive for Research in Archetypal Symbolism in NYC in the spring of 2008.

— Valerie Lum